Homebound for months during the pandemic, I seized the first opportunity to travel beyond my dull domestic frontiers. This unique excursion was facilitated by the three day virtual Asian Women’s Film Festival organized by the International Association of Women in Radio and Television – India Chapter. Having been a student, researcher and occasional teacher of cinema, I could not have planned a better itinerary for myself other than that promised by the festival’s catalogue of contemporary women’s films. I felt particularly compelled to linger on two documentaries enmeshed in questions of home and exile.

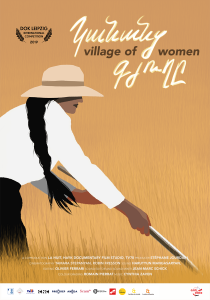

Village Des Femmes (Village of Women)

The first film, Village Des Femmes (Village of Women) directed by Tamara Stepanyan. leads one right into Lichk, a radiant yet melancholic Armenian village. Like a modern remnant of a twisted folk tale, this is quintessentially a village of women. All the working-age men spend most of the year in Russia to eke out a living. And in their absence the sturdy women of Lichk tend to everything, from land to animals, from children to the elderly.

We hear of the ‘exiled’ sons, husbands and fathers more than we see them. They figure as consistent allusions in every conversation, story and song exchanged in the village. What we do more intimately witness, is the everyday life of the women left behind. Though unlike their adrift husbands, the women are rooted, this enforced sundering of families renders their sense of home un-whole too.

Through the film, one experiences an inverted seasonal cycle in the village. Ironically, it is winter that is desperately awaited in Lichk, the only time the men return to their homes, whereas the arrival of spring, as the landscape begins to thaw, marks instead, loss and separation. Stepanyan’s film in this way beautifully conjures paradoxical emotional landscapes. In fact, all through the film, there runs a cross weave of light and darkness, of laughter and sighs, of separation and togetherness. The film also reminds us of the larger cycle of displacement and loss that frames Armenian history.

In spite of the extraordinary pathos enveloping the lives of these women, the film manages to capture a different truth as well. The film is brimming with shots of their ceaselessly laboring arms, kneading dough, swirling and baking bread, harvesting potatoes from the earth, stacking grass in open fields, picking apples perched upon trees, thus making full the ‘emptied’ village. We see from start to end, this community of women never passive, never resigned, but perennially creating meaning and nurturing life.

Docu short ‘Drapchi Elegy’ from the prisons of Tibet

Moving out from Village of Women, we find ourselves led into a more constricted enclosure in and Ritu Sarin and Tenzing Sonam’s short documentary Drapchi Elegy. Unlike the community spaces in Stepenyan’s film, this film is mostly inhabited by the solitary, often lonely presence of the protagonist. The camera follows Namdol Lhamo, a Tibetan refugee leading an ordinary day in the city of Brussels. Embedded within this ordinary day however, is Lhamo’s extraordinary history. In 1992, 28 year old Lhamo, along with a group of other nuns, was put into Drapchi prison for six years for peacefully protesting China’s hegemony.

While still imprisoned in the largest prison of Tibet, these nuns sang, recorded and smuggled to the outside world a series of powerful protest songs. In the film, we see Lhamo on the other side of this heroic trajectory, forging a life in Europe on her own, exiled from a home still struggling for freedom.

The film poignantly visualizes the experience of political exile, in the convergence of past and present. When we see Lhamo travelling in the city trains, we see the mundane visuals of her present European life. But the images of closed doors, framed windows and grab handles that uncannily resemble handcuffs, eerily echo her past captivity. They also make one wonder whether a sense of imprisonment grips her even today. The film also juxtaposes the two worlds Lhamo straddles each moment.

The visual and the audio track often converse dialectically. Belgian station names flash as Tibetan songs play, the city passes by as she is plugged into Dalai Lama’s sermons. Cooking, eating alone, her voiceover speaks of the comforting community of prisoners back in Tibet. In the film we see her both as an active, healthy survivor, as well as one plagued by hidden wounds.

Emblematic of her continuing exilic status, Lhamo is depicted in constant states of motion, whether in trains or on foot. This movement also signals the emotional and spiritual journey she is consciously undertaking with each forward step. Her trauma fails to paralyze her. Moreover, the sense of unceasing motion in the film reminds one that the struggle for Free Tibet is still underway. Homebound for months, witnessing the journeys of these women, will remain unforgettable for me.

Arundhati Sethi

Arundhati Sethi is a Mumbai-based freelance teacher and researcher of Literature & Cinema. Her research interests include Postcolonial, Migration Studies as well as the intersection of Visual and Literary Studies. She aspires to pursue her doctoral study in these very areas. She dabbles in writing poetry and is also pursuing the Indian classical dance for of Odissi.

![Powerful Pride documentary Legendary Children [All Of Them Queer] streaming very soon](https://globalindianstories.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Legendary-streaming-release-featured-238x178.jpg)

![Powerful Pride documentary Legendary Children [All Of Them Queer] streaming very soon](https://globalindianstories.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Legendary-streaming-release-featured-100x75.jpg)