The 2nd of May is the birth centenary of one of the greatest maestros of Indian cinema, the legendary Satyajit Ray. Regarded as one of the distinguished filmmakers of the century – Ray was a Calcutta-born filmmaker known widely for his genius as a one-man powerhouse for his films as the author, lyricist, screenwriter, music composer and graphic artist.

Ray had to compete and share platforms with stalwarts like Akira Kurosawa and Ingmar Bergman to take Indian cinemas to the Oscars with his film Panther Panchali. At that time, he worked on absolute shoestring budgets and with rudimentary technologies that were available in the Indian film industry. However, despite the challenges, his films got the recognition and his team continued to win in festival circles, making the world take notice of Indian cinema.

I was one of the lucky Ray fans who got to visit Ray’s home in Kolkata, interact at length with his son, Director Sandeep Ray, while sitting in the maestro’s living room as an Entertainment Producer with Star News. Making special episodes on Ray’s birthday was one of my favourite projects, something I looked forward to every year, feeling fortunate to shoot and interview the technicians he worked with, his son and family and spend some hours in his home.

After one such shoot, Sandeep Ray was kind enough to let me walk into the legend’s study. Obviously cameras were not allowed, and while my crew waited outside, I was allowed to open my shoes and step into Ray’s most intimate and creative space. He scripted, composed, designed and sketched his own film storyboard in this space and I remember getting goose bumps simply being there, taking in the energy and smell of the room, much of which was left as is after his demise.

As a huge Ray fan, my next tryst with Ray’s artists was at the 7th London Indian Film Festival (LIFF) in 2016, when The Best Short Film award was dedicated to the maestro (and has been continuing since) and an evening of masterclass on Ray’s work was taken by the legendary actress, and Satyajit Ray’s favourite Sharmila Tagore, at the Cineworld in Haymarket, London.

In discussion with London-based director Sangeeta Datta, the evening was a complete delight for Ray fans, filled with exciting anecdotes on Ray at the various shoots and the relevance of his movies after nearly six decades – making them timeless classics of world cinema.

The following bit is my report for www.bollywoodjournalist.com, filed a few years back but is still evergreen in its content and facts. This is a take on two important icons of Indian cinema – the Director Satyajit Ray and an artist he worked with over two decades, Sharmila Tagore.

Sharmila started her career at the age of thirteen with Satyajit Ray’s Apur Songshar (the third part of the Panther Panchali trilogy).

Sharmila Tagore and Soumitra Chatterjee in Apur Songsar

“I acted in a film before I could even see a film. Films were frowned upon in those days and many families did not want their daughters to work in cinema,” she said.

“My elder sister Tinku had worked as a child artist in Tapan Sinha’s Kabuliwala in 1957. So Manikda (Satyajit Ray) was sure I would be allowed to take on the role of a teenage bride in his trilogy Apur Songshar.”

Written by Bengal’s renowned writer Bibhutibhushan Bandhopadhayay, the story was set in the 1920s urban Bengal. But even after nearly a century, Apu and Aparna’s love story remains magical and eternal.

“This was made at a time when youngsters did not set up home on their own. They would be with their in-laws or extended families. But in Apur Songshar it was just the two of them. So their story with all the turns and turmoils is relevant today.”

The movie Debi – set in the backdrop of 19th century India is a tragic story where Dayamoyee (Sharmila) becomes a victim of his father-in-law’s superstitions. An arch devotee of Goddess Kali, he dreams that Kali has incarnated in his daughter-in-law Dayamoyee, the young bride.

She is robbed of her life and gets worshipped as the Goddess Kali.

Sharmila Tagore in Satyajit Ray’s Debi

“Women and children continue to remain as the first victims of religious orthodoxy worldwide. The film came under criticism as an attack on criticism of the Hindu religion, but saw the light of the day,” said Sharmila.

“It did not do well in the box office, but was not canned like it would probably have been, in today’s backdrop of religious rifts.”

The female and children victimization is relevant as it is being repeated in conflict situations worldwide in our modern times.

Women have been celebrated in their different shades in Ray’s classics – from the stubborn and silent defiance of a young girl in Postmaster, to the stiny melancholy of a lonely housewife in Kanchenzunga singing ‘E parabashe robe ke’ (who wants to survive in this desolation) by the mall. Ray has also portrayed women as human beings with human frailties – struggling with extra marital affairs, struggling with their identities as society keeps on imposing their own demands from her.

Sharmila said that Ray was facing criticism for making apolitical films in a turbulent Bengal of the 60s and 70s. This was one of the main differences between Ray and his peers like Mrinal Sen.

It was around that time that he started the Urban trilogy and Sharmilla found herself playing the role of the idealist Tutul in Seemabaddha – a film looking at the other world, the life of a corporate executive who falls from grace in the eyes of his sister in law at the same time that he secures corporate ascendance.

A caustic comment on the corporate world with a beautiful metaphorical end of the protagonist climbing up the (corporate) steps only to wait for his end. The more he climbs (the lift is out of order), the more exhausted he becomes till he reaches his destination – shorn of all dignity and morality.

“Ray was a pioneer in natural cinema. He changed the overtly dramatic dialogue deliveries to natural conversational dialogues. He pioneered the use of location sound. The use of the train sounds, that runs through Apu’s triology, the tap water running and the use of surround sound to weave into the story was invented by him.”

This was a time when shooting indoors with floor lights was really difficult. His cinematographer, the legendary Subroto Mitra discovered and introduced the use of the bounce light.

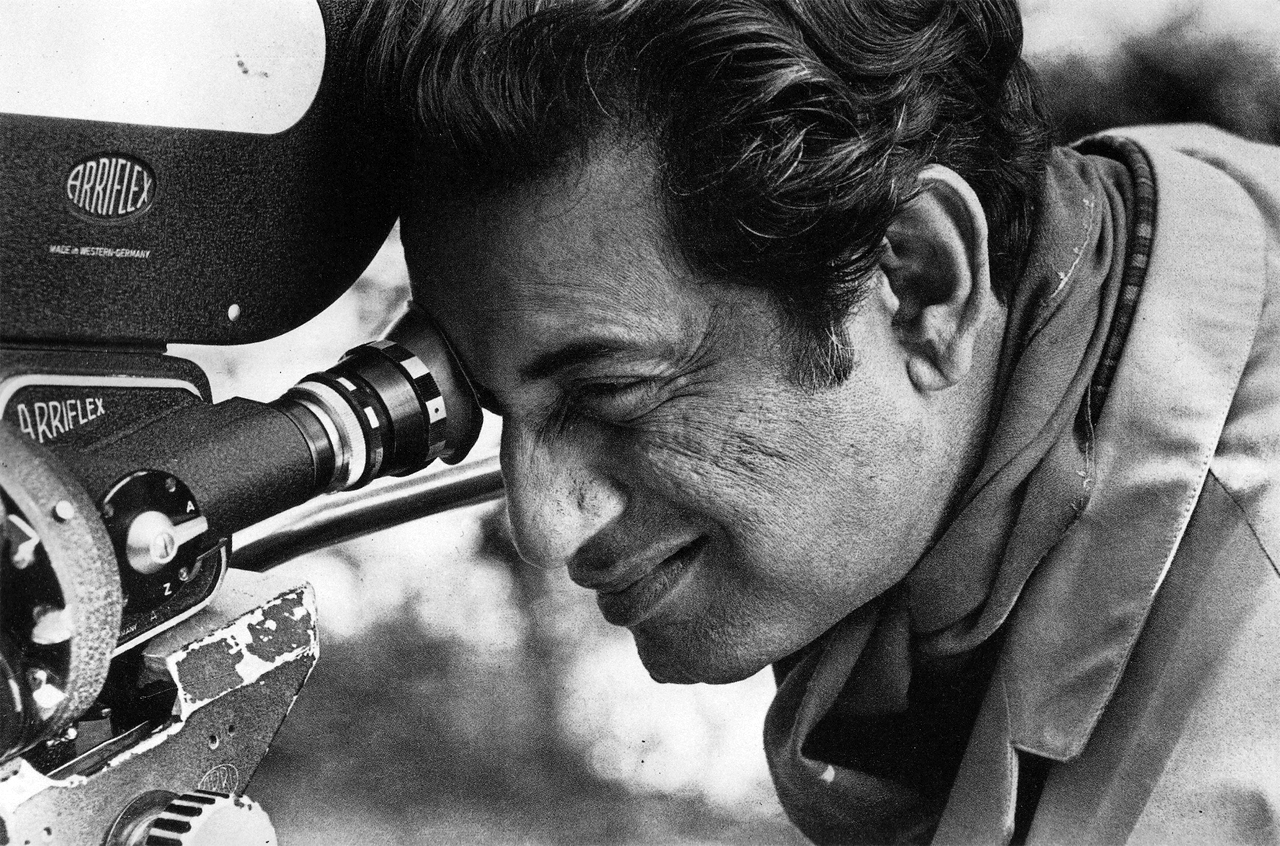

While shooting the film Aranyer Din Ratri, Satyajit Ray went fully solo for economic reasons. He could not hire a cameraman and shot solo with an Arriflex.

“Films were expensive those days and we had to get the shot right in the first or the second take. He did a trolley shot alone and using his intuition, he got it right in the first take” Sharmila said.

That was the kind of genius he was. “Tiger (Tiger Patuadi) used to say that ‘Manikda was a person who even God would call God’.”

“He gave us hand written scripts bound in green leather (because of the tight budgets he worked on) and we treasured those as masterpieces. He scketched all the scenes himself.”

“Although we were given scripts beforehand, we were not allowed to memorise them. Only Rabi (Ghosh) da was allowed to improvise. He would break into a song in the middle of a scene, to add to the comic character.”

Sharmila Tagore

“At the end of the shoot, we would go and drink ‘mohua’ with the santhals, dance with them and reveal in the simplicity and beauty of their lives. But these areas have now turned into Maoist dens and we do not have access to them any more. “

This film was Ray’s effort to understand the youth who live in a vacuum – in some kind of imperial superficialism. He brought to light that women in tribal India also shared a drink with the men, danced with them and Indian villages could be as poetic and beautiful as Europe.

Ray’s films were accepted graciously worldwide. “ When it was screened in Paris, everybody would burst out laughing when they saw Rabida (Rabi Ghosh) in Aranyer Din Ratri,” Sharmila said.

Satyajit Ray is rightfully credited with putting Indian cinema on the world map. What is probably less talked about, is the fact that he has put Indian women in the world map too. He has celebrated womanhood in all its complexity and multi-hued beauty, from the raw, earthly fragrance of the tribal Duli (Simi Grewal) to the young bride (Sharmila herself) who begins to wonder if she is human or a goddess – a tapestry unparalleled has been crafted.

We mere mortals, can only sit back and wonder!

Smita is a multi-cultural freelance journalist, writer, and filmmaker based out of the US, London, Hong Kong, and India. Global Indian Stories is her brain-child. Created to chronicle diaspora stories written by Indians of all age groups, from different walks of life across the globe, Smita makes sure that the platform remains inclusive and positive.

![Powerful Pride documentary Legendary Children [All Of Them Queer] streaming very soon](https://globalindianstories.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Legendary-streaming-release-featured-238x178.jpg)

![Powerful Pride documentary Legendary Children [All Of Them Queer] streaming very soon](https://globalindianstories.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Legendary-streaming-release-featured-100x75.jpg)